Newly released FBI records reveal that Richard Masato Aoki, widely revered as a radical hero in the San Francisco Bay Area in the 1960s, was deeply involved as a political informant for the FBI, informing on his fellow Asian activists and on Black Panther Party leaders Huey Newton and Bobby Seale.

Going beyond previously disclosed FBI records, the documents show that while acting as a militant leader, Aoki covertly filed more than 500 reports with the FBI between 1961 and 1971 on a wide range of activists and political groups in the Bay Area.

Aoki was a well-known figure in the Bay Area’s activist community and an early member of the Black Panthers who publicly acknowledged giving them some of their first guns. After he died in 2009 at age 70, he achieved new notoriety with the release of a feature documentary about him and a biography. Neither work mentioned his relationship with the FBI.

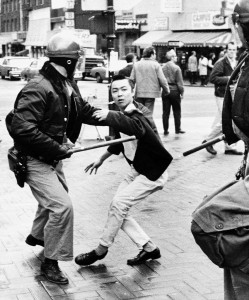

A young Richard Aoki is involved in a 1969 protest at Telegraph Avenue and Bancroft Way near the UC Berkeley campus. Credit: Courtesy of the Oakland Tribune

Although incomplete, the records show that FBI agents considered Aoki a valuable informant with “top level” access to the Panthers. The bureau assigned him a “confidential source symbol number” to protect his identity – SF 2496-S or sometimes SF 2496-R – and took extra security measures. One document said disclosure that he was an informant could “have an adverse effect upon the national defense interests.”

Aoki had said publicly that he gave the Panthers some of their first guns, which Seale confirmed in his autobiography. The Panthers openly and legally carried guns obtained from various sources on their “community patrols” against police brutality. Their use of weapons publicized their cause but also led to heightened law enforcement scrutiny and fatal shootouts with police.

However, the newly released records do not indicate whether the FBI was aware of Aoki’s role in arming the Panthers or whether the bureau was involved in it. If the FBI knew Aoki was arming the Panthers, or was involved in that, it would raise questions about whether the bureau was attempting to foment violence that would discredit the Panthers or set them up for a police crackdown.

The Panthers became a major target of such dirty tricks under the FBI’s unlawful COINTELPRO operation, as Congress later found, but there is no indication in the released records that Aoki was knowingly involved.

Carol Cratty, an FBI spokeswoman in Washington, declined to comment for this story.

The newly disclosed documents provide more information about Aoki’s informing but raise more questions about his true role. Some of his friends, such as Belvin and Miriam Ching Yoon Louie, have contended that although he began his informing at the behest of the FBI, he eventually became radicalized and he “flipped.”

The records show that Aoki informed on the Black Panther Party; the Asian American Political Alliance; the Young Socialist Alliance; the Socialist Workers Party; the Red Guard, a radical group in San Francisco’s Chinatown; and the 1969 Third World Strike and several other campus political groups at the University of California, Berkeley.

He named dozens of people as being members, attending political meetings, giving talks or writing unsigned articles. As a result, many were indexed in FBI files for future investigation.

Some of the information he provided appears to have come from public sources, such as newspapers, leaflets or rallies. Other information seems innocuous. If his friends’ theory about his being radicalized is correct, Aoki could have been feeding the bureau relatively harmless information with more private information mixed in.

Harvey Dong, a longtime friend and executor of Aoki’s estate, said in an email that based on the partial records released by the FBI over the years, he remained convinced that Aoki had become a true revolutionary by the time he joined the Panthers. “The documents themselves show that he did not fully cooperate with his FBI handlers, with much of the information [he] disclosed in the realm of public knowledge. The documents themselves leave open that he made efforts to side with the movement when sides had to be chosen,” he said in the email.

Seale; Elaine Brown, a former Black Panther chairwoman; and Elbert “Big Man” Howard, an early member of the Panthers, did not respond to emails seeking comment. In 2012, after the first story about Aoki’s FBI involvement was published, Seale told a community forum in East Oakland: “This here is a defamation against my friend, my comrade.”

In the 1960s at UC Berkeley, Aoki cut an imposing figure, wearing slicked-back hair and dark glasses even at night. He was born in San Leandro in 1938 and was interned at the age of 4 during World War II with thousands of other Japanese Americans. After the war, he grew up in West Oakland, in what had been known as “Little Yokohama” but was then a low-income area populated by black migrants. He joined a gang and became a tough street fighter, he later recalled in interviews.

Aoki enlisted in the Army at age 17 and began service immediately after graduating from Berkeley High School. He had hopes of becoming the Army’s first Asian general and was fiercely anti-communist, he said. Within a few years, he was an informant in J. Edgar Hoover’s sweeping investigation of suspected subversion, which Congress later found included tens of thousands of people involved in lawful dissent and “spread to students demonstrating against anything.”

I discovered that Aoki had been an informant while doing research for a book about the FBI’s Cold War activities in the University of California system. When I interviewed Aoki in 2007, he denied he’d been an informant but added, as if by way of explanation: “People change. It is complex. Layer upon layer.”

When I first reported that he been an informant in 2012, some of Aoki’s colleagues and supporters expressed anger and doubt. Some even contended that the FBI was falsely labeling Aoki as an informant in order to posthumously discredit his radical legacy. An additional release of FBI records confirmed that he had been a paid informant for 16 years who used the alias “Richard Ford” in his reports, but the bureau heavily censored those records.

The FBI recently reprocessed more than 700 pages of those records as the result of a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit I filed in 2011 that asserted that the bureau used Aoki to conduct unlawful political surveillance of people engaged in legitimate dissent. The FBI said its activities were lawful but settled the lawsuit by agreeing to release information it had previously withheld on law enforcement grounds and paid $125,000 in attorney’s fees.

The newly released documents are FBI reports on various organizations and individuals that summarize intelligence from Aoki and other informants. (It should be noted that FBI intelligence reports often contain unverified information and errors.)

The earliest one is a Dec. 13, 1961, report on the Berkeley branch of the Young Socialist Alliance. It says Aoki named the organization’s officers and 19 of its members and informed on their private discussions about finances, relations with other political organizations and what causes to support. He also reported on the group’s public talks, including ones about Cuba’s “advances” under Fidel Castro and the “Decadence in the Modern Film.”

Aoki enlisted in the Army at age 17 and began service immediately after graduating from Berkeley High School.Credit: Courtesy of Harvey Dong

According to another FBI report, dated Sept. 21, 1962, Aoki attended a “vacation school” put on by the Socialist Workers Party at Big Bear Lake in Southern California. The report notes that Aoki complained to an FBI agent that his car had broken down on the way and his expenses exceeded the $125 the FBI had allotted to him.

In a third FBI report on the Young Socialist Alliance, dated Jan. 18, 1963, Aoki informed on internal factionalism and a talk warning members about the FBI. According to the report, Aoki reported that Paul Montauk, a Socialist Workers Party member, warned that the FBI “employs illegal methods” and deployed “an army of despised informers.”

The Socialist Workers Party later won a federal court decision holding that the FBI illegally had sought to disrupt it, burgled its offices and used members who were informants against it. “The intrusions of these member informants were serious, and of a substantial magnitude,” the court ruled.

In the mid-’60s, Aoki attended Merritt College (then known as Oakland City College), where he befriended Huey Newton, a pre-law student, and Bobby Seale, an engineering student, who were in a political group called the Soul Students Advisory Council. In fall 1966, Aoki transferred to UC Berkeley as a junior in sociology. About that time, Newton and Seale formed the Black Panther Party, and that winter and spring, Aoki gave them guns and firearms training, he and Seale have said.

Two of the newly released reports concern the Panthers, whose formal name was the Black Panther Party for Self Defense. One, dated Nov. 16, 1967, lists Aoki as “top level” informant SF 2496-S. He is frequently cited as a source in the report, and FBI officials deemed his position extremely sensitive. Had the Panthers known then that he was an informant, he might have been in grave danger.

The report states: “A supplementary T symbol (SF T-2) was designated for SF 2496-S (Richard Matsui Aoki) for the limited purpose of describing his connections with the organization and characterizing him. Because of the top level position of this informant this additional designation is considered necessary to insure protection of his identity.” (T symbols are temporary code numbers assigned to sources in reports. The report misstates his middle name.)

The document cites five instances in which Aoki gave information on the Panthers between May and November of 1967, paraphrasing him. Some of the information was innocuous or public.

According to the document, Aoki said that in early 1967, he was “drawn into the BPPSD and had the title of Minister of Education bestowed upon him.” He said Newton and Seale chose him partly because he had been chairman of a campus civil rights group.

Aoki told the FBI that the Panthers were formed as a militant black political organization to combat police brutality, to unite black youth to determine their own destiny and to educate black people in African history.

The Panthers’ political philosophy, he said, included ideas from Mao Zedong (whose name sometimes is spelled as Mao Tse-tung), Malcolm X and the writer Frantz Fanon. But he said only Seale, Newton and he were fully aware of this, and besides Eldridge Cleaver, no Panthers seemed informed or interested in the group’s philosophy.

Although the Panthers sold a little red book titled “Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-tung” to raise funds, Aoki told the FBI that they did not advocate communism and had no communist members, according to the report. However, he said they opposed the existing social order as racist.

Aoki said the Panthers’ total membership was 40 to 100 people, and he estimated that 15 members openly carried guns in public. He added that Newton was urging members to get guns, and as the report put it, “it was recommended” that hand weapons be .38 caliber or above, and that shotguns be 12 gauge.

Aoki advised the FBI that the Panthers were recruiting new members and that the leadership estimated they had acquired at least 1,000 “paper members.” He said Newton kept membership records in his personal possession. He gave the FBI the address of the woman with whom Newton was living.

Aoki also informed on some of the Panthers’ internal and external conflicts. He named the six men on the organization’s executive committee as of that July, reporting later that Cleaver had broken away because of differences with Newton and Seale over policies. That month, Aoki reported on a potential merger between the Panthers and the unrelated Black Panther Party of Northern California, noting that the plan broke down and the Panthers assaulted some members of the other group.

Aoki also provided intelligence that the FBI used in its security investigation of Seale. In a lengthy report on Seale dated Nov. 30, 1967, Aoki was one of several informants. He again was assigned two T symbols because of his “top level position.”

According to the report, Aoki told the FBI that as of July 1967, Seale was receiving welfare payments and working full time as chairman of the party, then based at 5624 Grove St. in Oakland. He also reported that Seale and his then-wife had separated and that she and their infant had moved in with her parents, it said.

Aoki might not have known, but this was the kind of intelligence the FBI could use to unlawfully disrupt the Panthers, an effort that would become a major counterintelligence operation the following year, according to reports by the U.S. Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities.

J. Edgar Hoover declared in September 1968 that the Panthers, who by now had chapters across the nation, posed “the greatest threat to the internal security of the country.” He cited their radical philosophy and armed confrontations with police.

As part of the unlawful counterintelligence operation to stifle dissent, the committee found, the FBI used informants to gather intelligence leading to the weapons arrests of Panthers in Chicago, Detroit, San Diego and Washington.

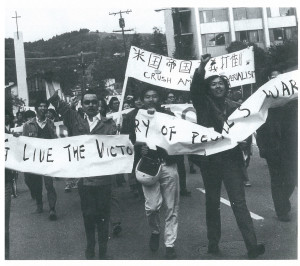

Aoki (left) represented the UC Berkeley Asian American community as part of the Third World Liberation Front strike. Credit: Courtesy of Nancy Park

However, there is no indication in the released records that Aoki told the FBI that he had given guns to the Panthers, or that the bureau knew about it. If Aoki had done so without the FBI’s knowledge, he may have feared that reporting it might have angered the FBI and the Panthers. The FBI formally ended COINTELPRO in 1971.

Nor is there any indication in records released to date that Aoki told the FBI of his involvement with the Panthers prior to May 1967, some six months after he knew of the organization’s founding. The records contain no report from him about the Panthers’ controversial May 1967 trip to Sacramento in which several were arrested for openly carrying guns into the state Legislature to protest a law restricting public firearms displays.

According to Seale’s statements at a public forum in 2012, Aoki had distanced himself from the Panthers, saying he needed to focus on his studies at UC Berkeley. Previously released FBI records say Aoki was spending more time on school work and that his informing focused on political activity on campus, the specific subject of which was redacted.

However, the newly released records show that starting in early 1967, Aoki infiltrated a campus organization called the Tri-Continental Progressive Students Committee, whose participants included several foreign-born students. Tri-Continental urged national and international campaigns to end the war in Vietnam.

With his radical credentials by then well established, Aoki won election to Tri-Continental’s steering committee, and over the following year, he informed on the group’s officers and activities.

Three of the newly released reports concern the Asian American Political Alliance, a nonviolent civil rights group founded at UC Berkeley in 1968 to oppose racism, the Vietnam War and U.S. “imperialistic policies.”

The group aimed to break the silence of what its members saw as all-too-conformist Asian American communities. It supported the Black Panthers and other minority “liberation” groups. The FBI investigated the group as a potential threat to internal security.

A Jan. 23, 1969, report on the Asian American Political Alliance states that it is classified “Confidential” to further protect the identities of informants, especially Aoki, “who is furnishing valuable information on a continuing basis in the Racial and Internal Security fields.”

According to the records, Aoki in June 1968 told the FBI that the “Yellow Power” group recently had organized at UC Berkeley. He described the group as liberal rather than radical, and identified its participants as conservative, moderate or militant, placing himself in the latter category.

Over the next 18 months, Aoki filed at least 25 reports with the FBI on the Asian American Political Alliance’s internal operations, marches, meetings and conferences, and its officers and participants. He named a number of people who had signed articles in the group’s newspaper and other publications only with their initials.

The FBI listed some people he named in its domestic intelligence indices and used the information in what became a nationwide investigation of the group as it established chapters at other schools.

No comments:

Post a Comment